You may not know this: Lithuania was at one time known for its international cuisine. That was back in the early 1960s when my father, as head chef of the Francis Room — the dinner theatre experiment of Fran’s Restaurant was being publicized as a cosmopolitan culinary expert. Since our family name was considered awkward he was reinvented as Mr. Leonard. It was the sort of fabrication a small brochure might make about its staff back in the day when most people, unfamiliar with any of the Baltic nations, knew little about those countries’ culinary culture or subjugation to the Soviet Union.

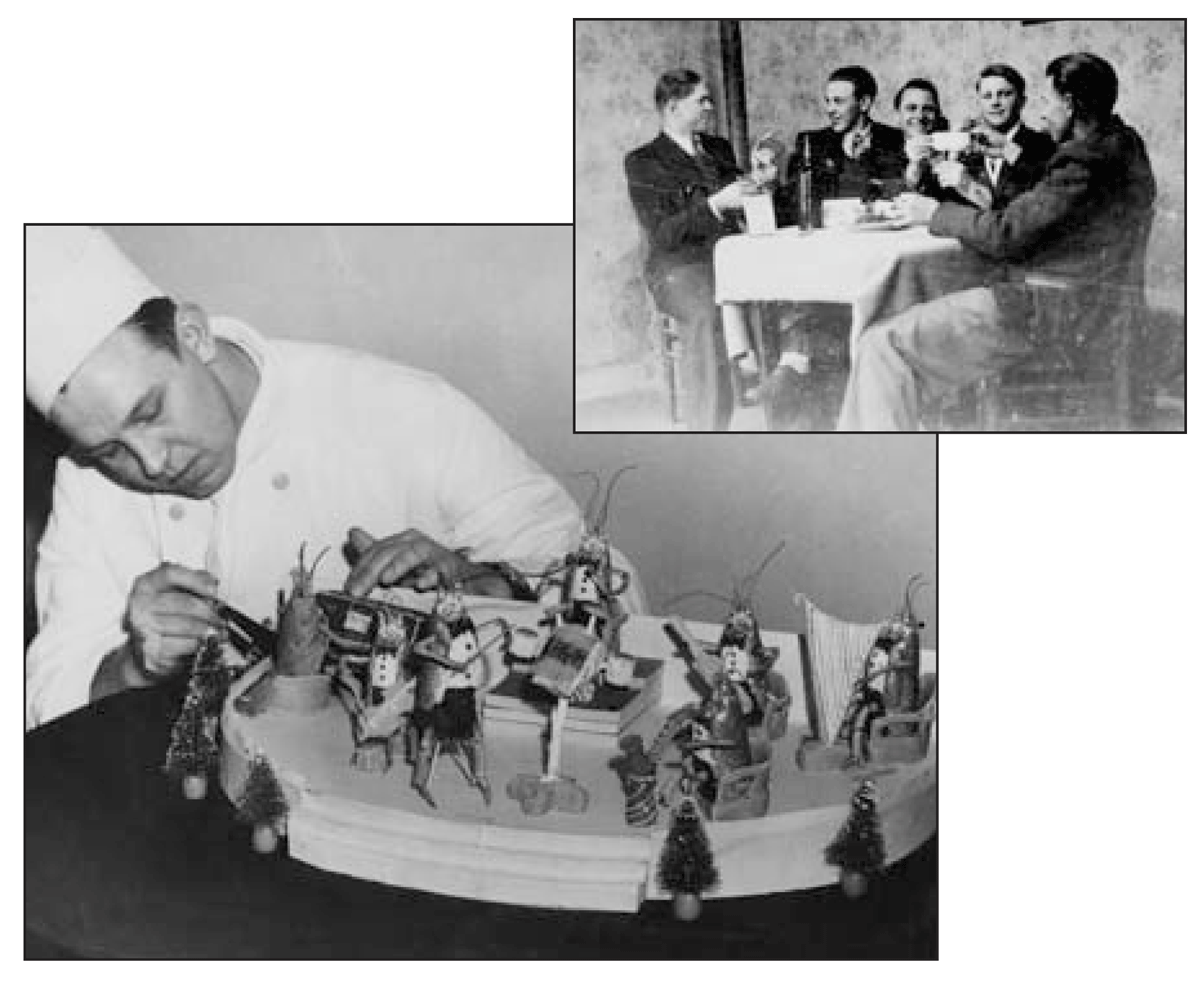

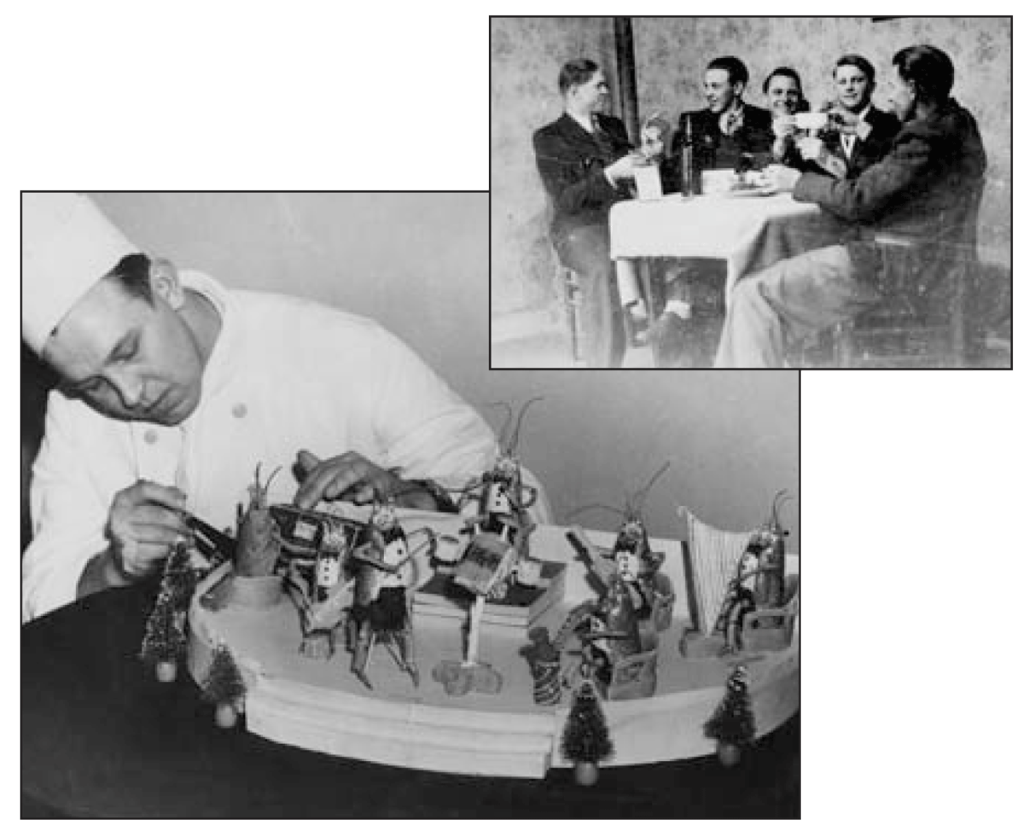

Left: “Mr. Leonard” with his lobster creation. Top: Leonardis Zyvatkauskas (2nd left) with friends in post- war Berlin.

But this piece is not about the old country or even the old restaurant; it is about impressions left by a father that extend beyond the Hallmark Card Day soon approaching.

My father, Leonardis Algirdas Zyvatkauskas, was a person of sharp contrasts. Of his halcyon days as a chef I remember a thoughtful picture of him with a food display of lively looking musicians that he crafted from lobster shells and another of him in cavalier fashion enjoying cigarettes and booze with his buddies in a post-war displaced persons camp. On one day he taught us how to create roses from pink icing sugar — on another he told us how to escape from capture by using the grate of an iron stove top. In the late 1950s we terrified onlookers by roaring around the Lake District in a sidecar pulled by his speedy Vincent motorcycle, and yet he would stop the chase to save a small animal crossing the road. One such creature, a small hedgehog, we kept as a pet.

The tales he told of life before England were not printable by “Toronto’s Home of Fine Family Dining.” Fran’s may have publicized his Lithuanian heritage as one of European culinary excellence but we knew otherwise. Through my father’s fantastic stories we knew the old country had a heritage of devils that lived in ditches at the side of raggedy country roads; that our family history included a Cossack uncle who rode in the guard of Tsar Nicholas II; and that there was an army of Bolsheviks who tried to shoot him. We knew that the countryside was populated with mysterious giants who slept in massive earthen burial mounds. We knew that the world was in a state of flux, largely on account of the Second World War.

My father was so expert at mimicking the sounds of bombs dropping and shrapnel exploding that we were in a constant state of concern about air invasion. To excite our imaginations he had three maxims for living — don’t sign any papers, don’t join any clubs and don’t let anybody into the house.

Eventually we learned that the devil at the side of the road was a man dressed in a cow’s skin with nails tied to his fingers. Also that the older brother whom my father admired for his heroics in the Battle of Leningrad had all signs of his Red Army military insignia removed by a photographer’s airbrush so strangers would not confuse our family with communists. And the mysterious giants? They were merely tall medieval warriors, probably the forerunners of today’s Lithuanian basketball team.

Of the future my father would say “this is the age of telephones” and so we were discouraged from using these devices for flippant teenage talk. Of the past he said he would never go back to the old country — not even if he was paid.

At his funeral the priest insisted that as Brother Leonard was mounting the hill to heaven the saints were preparing to shake his hand. We knew this was just a story told by the church, much like the one told by Fran’s. Mr. Leonard had no time for saints; rather than shaking their hands, he would have turned to the other prickly characters who weren’t allowed beyond the pearly gates.

This article originally appeared in the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO BULLETIN • WEDNESDAY, MAY 26, 2010